Inequality and Exclusion by Government Design

By Dr. Jowel Canuday, Ph.D. and Dr. Estelle Marie Ladrido, Ph.D.

Kathanor and the Unequal Distribution of Aid

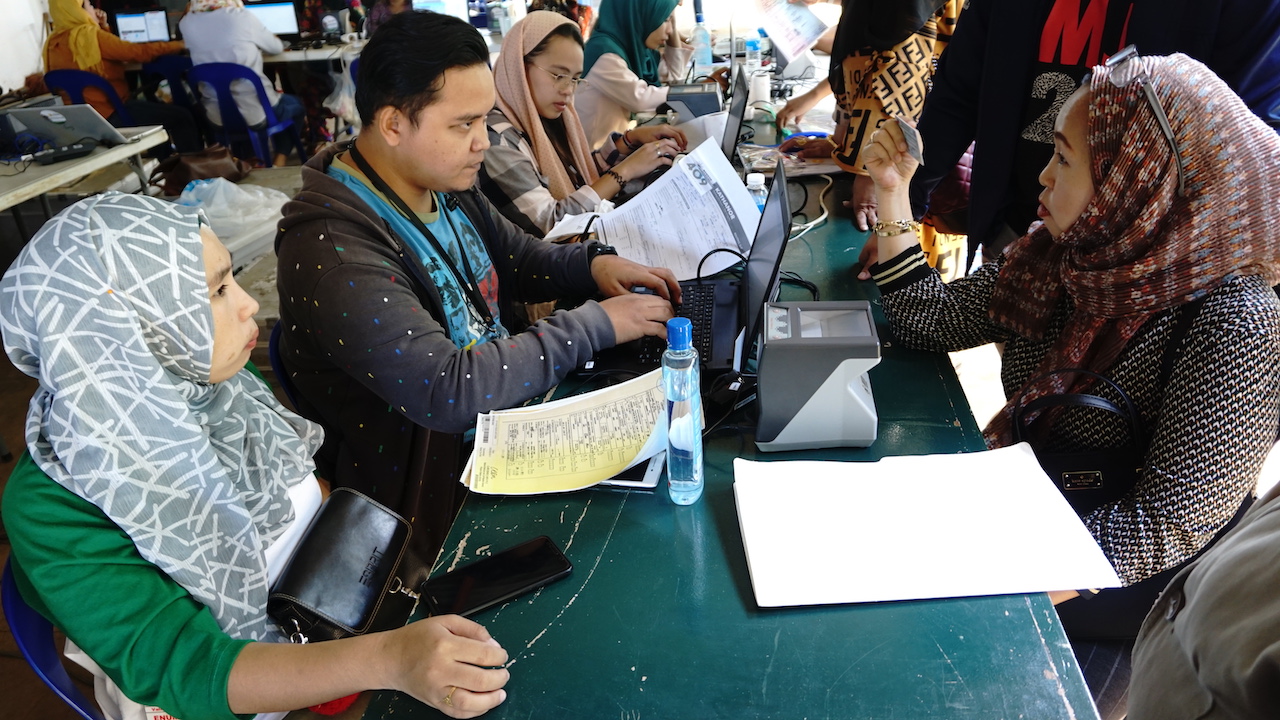

Emran Mabaning, an ambulant vendor and a father of three from the devastated community of Moncado Kadingilan inside Marawi’s so-called Ground Zero, has repeatedly queued to submit himself to the biometric data gathering operation initiated by Philippine government and the United Nation’s World Food Programme (WFP) on the golfing grounds of Marawi Resort Hotel inside the Mindanao State University campus.

The biometric data recording is a crucial documentation procedure ordered by the Task Force Bangon Marawi (TFBM), the coordinating agency organised by President Rodrigo Duterte to spearhead the Marawi City post-conflict recovery, to digitally record biological features including facial attributes, fingerprints, biographical history, and residential origins of all the Internally Displaced Persons (IDP) from the place.

This digital recording of biometric information, which the Task Force referred to as the Kathanor, serves as the basis for determining IDP eligibility in accessing future post-conflict recovery assistance to be extended by the government, the UN humanitarian bodies, and other intervention groups. Further, this allows TFBM to create a centralised database of IDPs that was intended to improve the efficiency of aid distribution, as well as facilitate the accountability of humanitarian agencies. In order to enlist for Kathanor, the IDPs made their way to the TFBM headquarters located at MSU, or else to the Marawi City Hall, upon receiving a message regarding their eligibility to take part.

Yet each day that Mabaning tried to register for the Kathanor, he repeatedly received a familiar thumbs down because the screening staff could not find his name and other pertinent records in the digital list of internally displaced persons on their laptop computers. Mabaning swears by Allah that he and his family lived in Ground Zero before the siege, and were displaced from the five-month armed encounters between government troopers and the reported Islamic State fighters.

He explained to the screeners that his name may not have appeared in their list because he purposely did not register himself or his family to secure aid in the immediate aftermath of the conflict. Instead, Mabaning took his family to temporarily live among relatives in Manila, using the little money he managed to take with him during the evacuation, because he could not bear to see his children and wife living in the extremely hard pressed conditions in the evacuation centers. His plea before the Kathanor biometric screeners went nowhere, and he echoed what the staff emphasized: “If my name is not on the computers, then they will not consider me an IDP.” Like thousands of other Marawi City IDPs, Mabaning has joined the ranks of those unable to access aid despite his insistence that he was a resident of Marawi, because he could not provide evidence to support his claim.

It was the same for Nurhaya Dimaukor, an elderly resident of Moncado Kadilingan before its devastation, who lived in the evacuation centers for the duration of the fighting and had listed herself in the government aid record. She availed herself of a Disaster Assistance Family Access Cards (DAFAC) issued by the Department of Social Welfare and Development, and which she had used to secure aid as proof of government recognition of her status as an IDP.

Arriving for biometric scanning, Dimaukor also brought with her documentation from the officials of Barangay Moncado Kadilingan attesting that she was indeed a resident of the shattered conflict zone and an IDP, in addition to utility bills and other listed documentation that should prove her residency. Like Mabaning, Dimaukor was turned down despite evidence of her residency and the aid documentation in her possession, on the grounds that there were no records of her in a “social cartography” mapping of pre-conflict streets, houses, and households that the Department of Environment and Natural Resources (DENR) had produced using satellite maps and ground-based survey. “There must be a mistake, but, I am going to follow this up with our barangay officials who attested to my residency,” Dimaukor said.

Jamalia Mutaib, a young mother who shared a home with married siblings and cousins in Norhaya Village in Marawi before its devastation, also presented her residency documents but was told that she could not proceed with the biometric screening, because she was not the owner of the house she lived in. She was classified as a sharer. The Kathanor biometric screenings prioritised those established as owners.

Mutaib’s neighbour and relative, Sinad, however, was accepted by biometric screeners and had her digital information recorded with TFBM. Having been established as a legitimate homeowner, Sinad’s biometric registration made her eligible to receive financial, material, and housing assistance from the government. Sinad’s experience of receiving a string of assistance packages was also shared by Hasana Digadademado, Omma Drumimbang, and Bashrun Ameer who were all homeowners in the devastated zones.

The fates of Mabaning, Dimaukor, Mutaib, and the other residents of Marawi represent the disparity of IDP experience in accessing humanitarian and recovery assistance from the government and aid agencies, where some residents are prioritised over others. Some were able to avail of assistance packages, while others were not. Apart from inequality in accessing aid, the Kathanor represents a far more fundamental and structural reason, which is the way Task Force Bangon Marawi designed its package of postconflict recovery assistance and projects. Not only has it contributed to the delay in the post-siege rehabilitation of the city. It has also revealed the complex relationships of kinship and residential arrangements that existed in Marawi prior to its destruction.

The Task Force had decided in May 2019 to halt all biometric recording over suspicions that system is being gamed by people misrepresenting the IDPs to avail of humanitarian assistance, as long queues of IDPs lined the streets of Marawi waiting to be scanned in exchange for aid. When it resumed in June, priority was given to owners, while some sharers were eventually able to avail of aid.

Owners, Renters and Sharers: Classifications for Aid Delivery

Secretary Eduardo del Rosario, over-all chief of Task Force Bangon Marawi, breaks down the IDPs in Marawi into three: owners, renters, and the sharers, arbitrarily distinguishing the displacement experience and suffering into these administrative categories. Each category of displaced persons was assigned corresponding value in terms of what they could access from government and international humanitarian intervention such as the United Nations bodies.

Houseowners are persons whose claims are supported by documentary evidence of ownership of the house within which several families could reside. Houses in Ground Zero are several floors high, and while there may be one established owner to the house, several families claim to have lived within that house either as renters or sharers. Once IDPs are established as houseowners, they were able to access a livelihood package from the Department of Trade and Industry (DTI) and Php 70,000.00.

A common complication among the IDPs emerged in the conduct of Kathanor. While families may have owned the house, and rented some rooms out for extra income, they did not own the land on which the house was built. This was the case for Diamond Sultan Gabriel, an IDP sheltering at the Sarimanok tent city. His house was built on property owned by the Pacasung family, and to whom he and his family paid an annual rent. He also said that they were given permission to renovate the house and to lease rooms. This became a source of livelihood before the siege. Gabriel shared that the Pacasungs are relatives from his mother’s side.

Renters are those who leased space within the property of an established owner. These could either have been residential or commercial spaces. Yet, as the case of Gabriel demonstrates, the line between owners are sharers can be blurry. What is clear though is whether one is an owner or renter, the siege resulted in loss of property and source of income, which should render them both eligible for aid.

Sharers are those people who made either residential or commercial use of the property but without having to pay rent. Sharers are often relatives of the houseowners, being allowed residence because of strong kinship ties. But despite their non-owning status, many of those categorised as sharers were able to receive the same aid as house owners: assistance packages from the DTI and as much as Php 70,000.00. Renters on the other hand, have not been given any assistance thus far.

These categories did not include landowners whose values were given greater premium in terms of access to post-conflict assistance. Of these categories, privilege is given to owners. Apart from receiving a more substantial aid package, TFBM has repeatedly stated that only they will be allowed to return and rebuild their homes on Ground Zero. In this way, they created a classification scheme that promotes aid inequality.

According to del Rosario, the privilege given to owners reflects TFBM’s efforts to correct the problematic issue of land and home ownership in Marawi City. Kathanor’s biometric screening is being used to establish whether one is indeed a legitimate resident of Marawi City, whether one was indeed a resident of Marawi City prior to the siege, where residency falls under one of three types. “So that the intervention of the government will be given to the right families, the right people,” del Rosario explained. Once ownership was established, then the claimants’ biometric data would be captured and stored as means of categorizing them, and determining their eligibility for transitional assistance. In short, owners got aid. “Once you are profiled and recognised as a resident, we have to give you assistance.”

While TFBM has requested for documents such as police clearances, and electricity and water bills as documents in support of establishing ownership, barangay captains have also been used to verify whether claimants are indeed residents, though del Rosario has also said that barangay captains can be conniving. Ultimately, TFBM fell back on determining the authenticity of documents, which for del Rosario is the reason for the slow down in aid delivery. “That’s the problem. So they are the ones making us have more problems and yet they are clamoring and demanding for the government to speed up and give them assistance.”

But the privilege given to ownership shows that the TFBM did not fully appreciate the complex living conditions within Marawi City prior to siege when they crafted their categorising scheme. Houseowners, renters and sharers are all able to claim residency in the city and are in danger of being permanently dislocated without proper compensation for property that had been lost or destroyed and receiving additional assistance along the slow hard road towards rehabilitation. In fact, it did not even consider the actual property owner in this categorization scheme.

Making Evacuees Fake: How IDPs Get Excluded from Aid

According to del Rosario, implementing Kathanor has been complicated by the discovery of duplicated or fake documents presented by the IDPs to receive the aid packs. He said that at the initial stage of the biometric screening, the DSWD reported that there were 98,000 families who claimed to have been displaced. Because of Kathanor, that number was reduced first to 78,000 and eventually to 45,000, as it allowed aid workers to identify those families said to have provided TFBM workers with false information regarding their family sizes in order to secure more aid packs. The reason why Kathanor was suspended in May 2019 was, upon realizing that it was attached to aid, the number of families requesting for aid, and presenting fake documents, swelled, even though they resided in areas outside Marawi. This raised the suspicion of aid free riders, those who are not really residents from the devastated area but are nonetheless claiming for assistance from TFBM. Del Rosario suspended the delivery of benefits until the issue of “fake evacuees”was resolved.

Those numbers conflict with those found in the Marawi City Master Development Plan, published by in 2018, which counted 127,309 persons displaced from Ground Zero, based on UNHCR figures, and those of the Asian Development Bank, which counted 369,196 persons displaced from Marawi City and neighboring towns. These figures roughly translate to 21,218 and 61,532 families respectively, considering that the population of Marawi prior to the siege was approximately 200,000. These discrepancies highlight the complexities of counting and subsequently classifying IDP’s into categories, when those categories did not fit the experience of the classified.

Further, identifying owners, renters and sharers is more complicated than presenting an authenticated barangay clearance or electric bill as proof of house ownership, especially if one looks at the movements of the IDPs immediately after the siege and their eventual return to Marawi once liberation was declared in October 17, 2017. While thousands of IDP’s were relocated to temporary shelters in designated tent cities around Marawi City, a good number of them took refuge with relatives across the country, in nearby cities such as Iligan and as far north as Manila, the Philippine capital. They were called home stayers, relying upon the strength of kinship networks as they awaited their return to Ground Zero, and who may not have been counted as IDPs in post siege aftermath. As one aid worker explained, “ “Ako, IDP ako. Relative ko ito. Nakikitira lang po ako.” He said the home stayers complicated the process of identifying Marawi’s IDPs, since they were spread across the country and were difficult to track down and count and distinguished the post-siege Marawi displacement.

In describing claims for aid, Del Rosario said that in applying for post-conflict assistance, many home stayers wrongly included these relatives in their applications, submitting fake documents to support these false claims. From the perspective of the IDPs, the claim for aid is not as cut and dried as del Rosario presents. The Meranaw core value maratabat refers to a sense of honor, integrity and sense of self worth. For home stayers, their dependence on the kindness of relatives was keenly felt as an imposition, demeaning to their self worth, and therefore a violation of maratabat. It was incumbent upon them to be able to reimburse their relatives, as demanded by maratabat, in exchange for the burden of having sheltered with them, even if temporarily. Including relatives in their Kathanor enlistment was not so much making a fake claim as fulfilling a cultural kinship obligation.

The implementation of Kathanor is on trend with humanitarian agencies efforts to systematize aid delivery as it allows for the creation of an IDP database that will identify those whom del Rosario has identified as “right, legitimate residents” of Marawi. This however implies that only those legitimate residents are deserving of aid. In segregating IDPs as houseowners, renters, and sharers based on their submission of authenticated documents, TFBM created a classification system that defined residency in quite limited terms and without an appreciation for the complex living arrangements that were often informed by kinship relations. By privileging houseowners, they created a system of unequal aid distribution, even though renters and sharers, often members of owners’ extended but impoverished families, were equally devastated by the siege.

In del Rosario’s view, apart from identifying legitimate recipients of aid, Kathanor, as it contributes to a database of Marawi residents, may have other bureaucratic benefits. He said that it could be a preliminary step towards a national identification system, and did not seem much concerned over issues relating to data privacy. Rather, correctly distinguishing legitimate aid recipients from fake ones, and preventing false claims seemed to take precedence in his formulations. The pressure then falls unto the IDPs to prove that they are worthy to receive aid.